In this world, there are places that with a single glance, make it clear that their history is unique. The Nakagin Capsule Tower is one of them. In its case, you can sense that this story does not seem to lead to a happy ending.

The tower is a clear example of retro-futurism, a bittersweet concept. Through retro-futurism, we can sometimes see what people in the past believed our present would be, as such we can decipher their expectations and their illusions. Unfortunately, one can’t control the people who will exist after you, and their beliefs. The future’s people may not prioritize the beliefs of those from the past. Even if those beliefs and practices were made to ensure a better future. The history of the Nakagin Capsule Tower is an example of this in practice, making it a sad story.

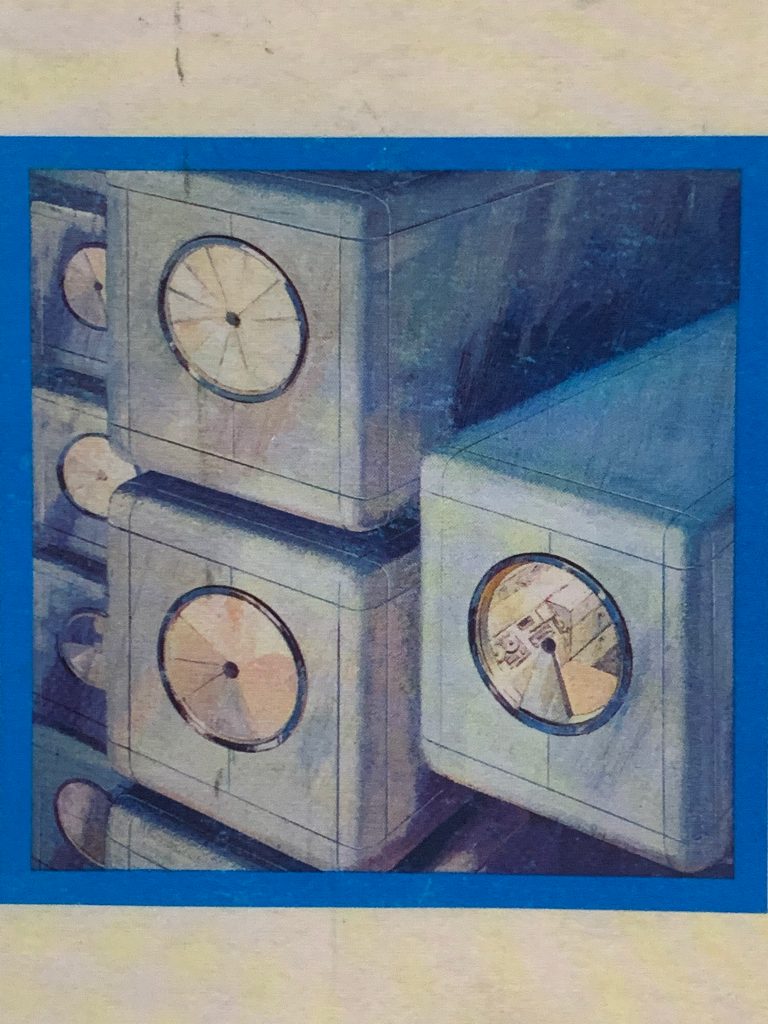

It was designed to evolve, always running parallel to the future. But that evolution never came: it became a costly complication. That is why today, after almost 50 years on its feet, the Nakagin Capsule Tower is dying. After years fascinated by the tower from the outside, on the last day of 2020, I decided to visit it from the inside and get to know its history a little better.

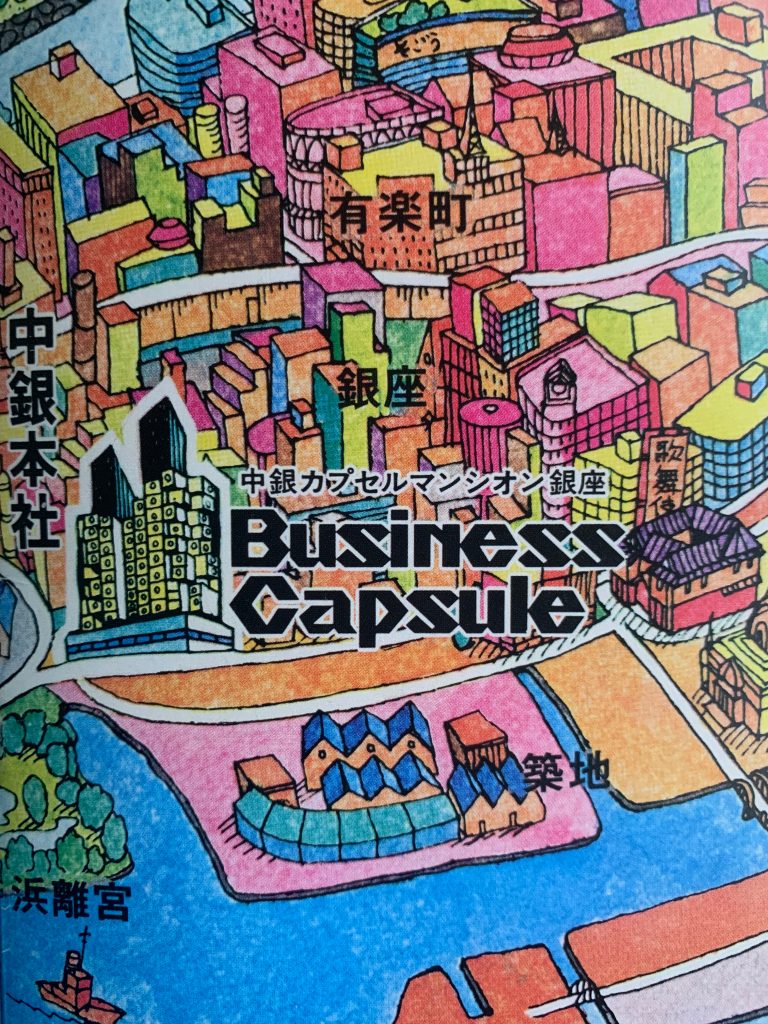

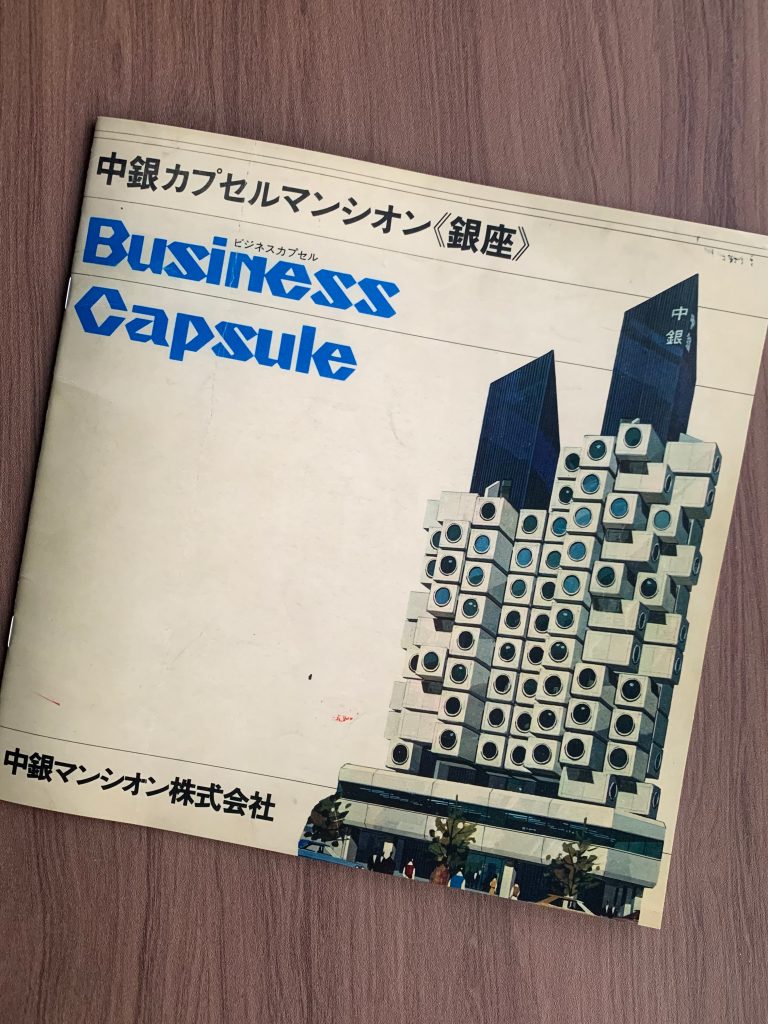

The architect Kisho Kurokawa was the one who designed the tower. At the Osaka Expo in 1970, he exhibited a type of building that could evolve, assembled from replaceable capsules. Entrepreneur Torizou Watanabe was looking to build an apartment building in Ginza that would offer businessmen a new experience, and Kurokawa’s idea fit with his vision of the future.

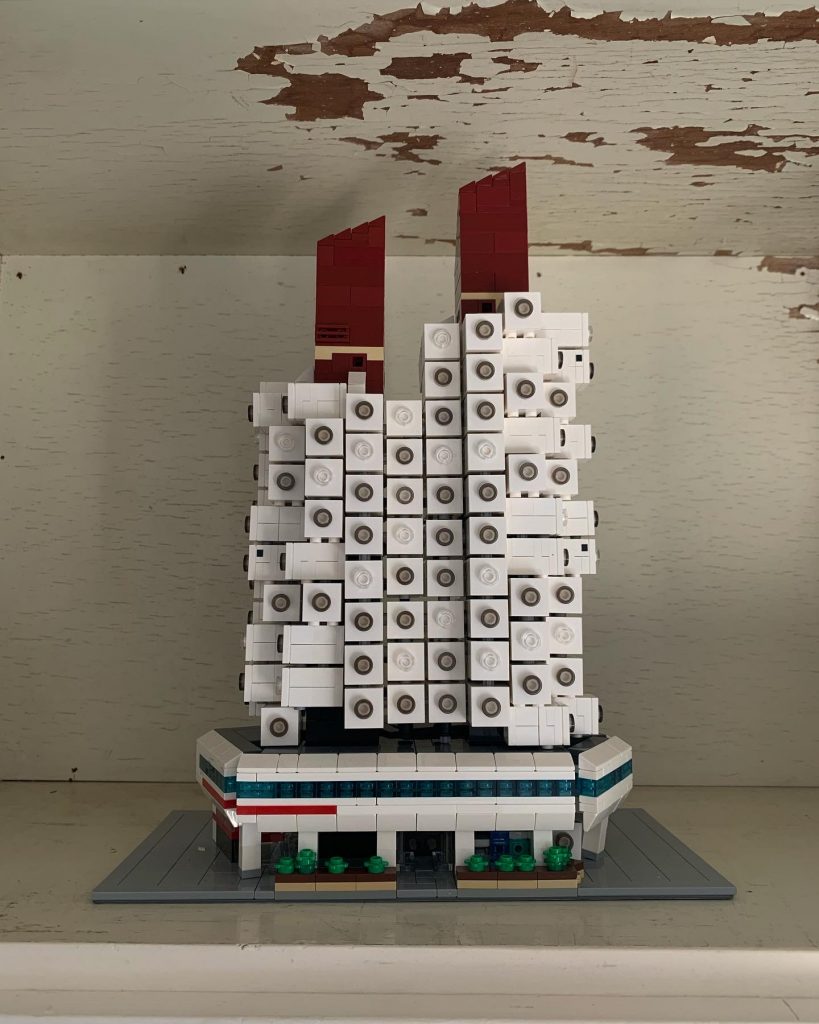

Kurokawa was part of the Japanese architectural movement known as Metabolism; based precisely on designing living buildings, thought to grow, and change according to future needs. Legend has it that Kurokawa was inspired to design the Nakagin Capsule Tower by watching his son play Lego — as a Lego fan I have decided to believe it.

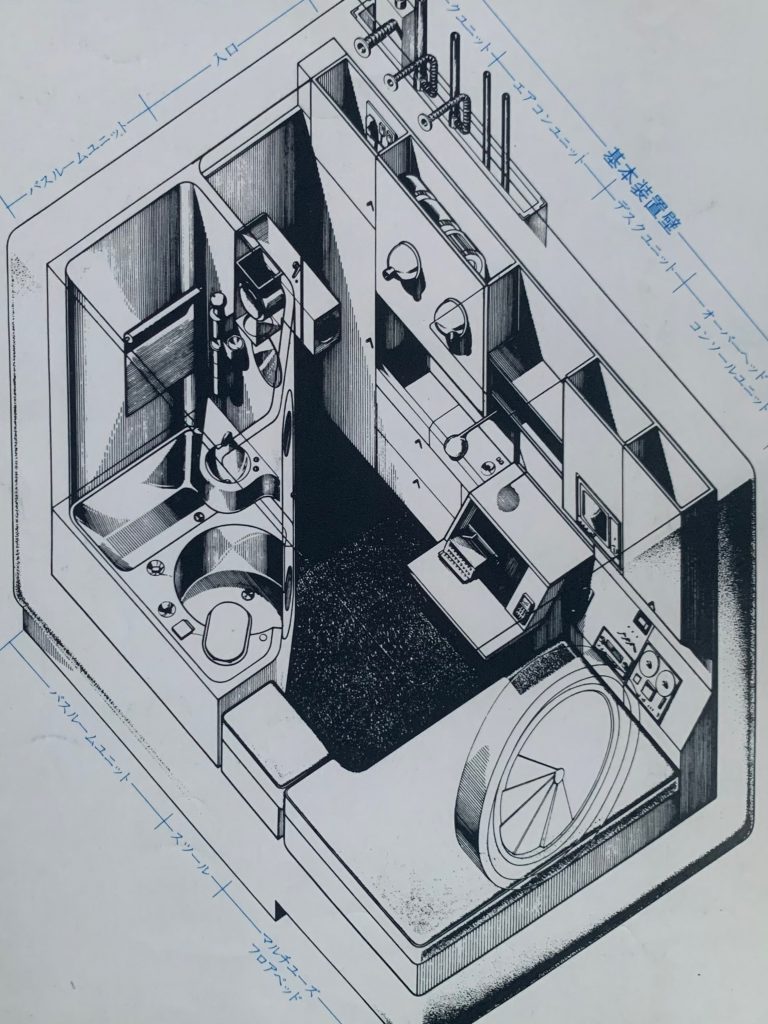

The tower was built in 1972 in just 30 days. Their 10-square-meter apartments had a bed, their own bathroom, a small kitchen, a folding desk, and state-of-the-art Sony equipment — “as if today you lived in an apartment with integrated Apple devices,” Yuka, my guide, explains. during the visit. The most emblematic: a circular window 1.3 meters in diameter. The feeling inside the capsule is that of being in the cabin of a cruise ship or in a spaceship. In the 70s there was nothing that represented the future more than space.

Businessmen started living in the apartments, usually only on weekdays. Initially, businessman Watanabe owned the entire building, but gradually, some capsules were bought by different tenants. Kurokawa’s plan called for the capsules to be replaced every 20 to 25 years, but this change never happened.

To make this change possible, all owners had to be willing to renew their capsules at the same time, since it is not feasible to remove them from the building independently. Although Watanabe owned a large part of the 140 capsules that make up the tower, an agreement was not reached between all the owners. For a building design to be new again, to start over from scratch, something like this marked the beginning of decay.

As early as the 1980s, water leaks started to be a problem. The rain remained on the capsule roofs without draining, damaging the steel. In 2010, a pipeline leak was discovered. In a normal building, this could be repaired, but in a building like the Nakagin Capsule Tower, where the pipes are installed in a very narrow space between capsule and capsule, this was too complex and expensive. It was from that moment on that the tower had no hot water supply.

The day before my visit to the tower it had rained. I was really able to experience what all those leaks do to the building. If inside the capsule you felt like you were on a boat, walking down the corridors and stairs, it was hard to believe that it wasn’t the case, due to the constant trickles of water and drips. Unfortunately, a ship cannot last long in these conditions …

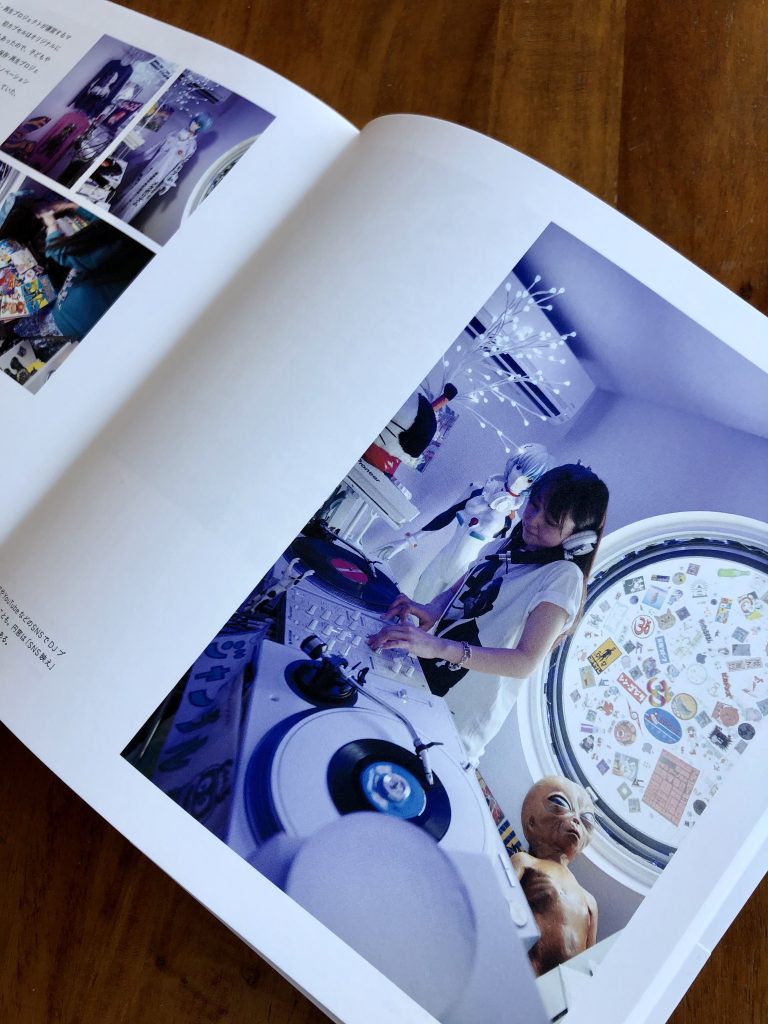

Even so, in those damp corridors, there were shoes, suitcases, decorations on the doors … There was everyday life. Of the tower’s 140 capsules, 20 are occupied by residents, 30 are used as offices, and another 30 are studios or workshops. Architects, designers, editors, CEOs, lawyers, university students, DJs, etc., use these capsules to live or work. Living or working in spaces of 10 square meters, in a building in such precarious conditions can only mean one thing: the tower fascinates you.

The rest of the capsules are abandoned. Inside some even wild plants have grown. “Isn’t anyone going to do anything for the tower?” I asked Yuka. Yuka is part of the Nakagin Capsule Tower Preservation and Restoration Project, an initiative promoted in 2014 by one of the capsule owners, Tatsuyuki Maeda, with the intention of saving the tower.

Yuka explained to me that Watanabe’s company sold the capsules that he still owned to an investment fund. This fund has been buying more and more capsules, with the aim of having enough decision-making power to demolish the tower and build a more lucrative building in its place. Currently, this fund owns 80% of the voting rights on the future of the Nakagin Capsule Tower.

The Tower Preservation Project also tried to get the Tokyo Government to classify the tower as a cultural asset on an exceptional basis, as this type of consideration is given to buildings that are 50 years old or older and the Nakagin Capsule Tower is now 49. The Tokyo Government rejected this proposal because it was a privately owned building.

Saving the tower requires a large financial outlay, but above all, it is important that the responsible entity understands the value of the tower, its meaning, and what it would have to become. Negotiations began with a fund that met these characteristics, but the coronavirus crisis has brought these negotiations to a standstill. Therefore, the tower is still in danger today.

In Japan, due to earthquakes and the building pattern, many buildings have a much shorter life cycle than in other countries. But preserving buildings of the past, especially if those buildings represented the future of an era, of a historical moment of bonanza, of creative freedom, and optimism, can be a great source of inspiration and knowledge for future generations.

I envy the people who have had the opportunity to make the tower a part of their lives. The crowdfunding book ‘Nakagin Capsule Style’ collects photographs and stories from 20 of the capsules that are inhabited as apartments or workspaces, and it is truly fascinating. In addition to the private capsules, some of the capsules are rented on a monthly basis, but the waiting list is very long. Some of the capsules were available on Airbnb, but this is not the case today.

What you can do and should do is visit the tower! Don’t just go into the building on your own — I was very surprised by the number of “Do not enter, call the police” signs that were everywhere in the building, so I understand this is common practice for some curious tourists. Sign up for a guided tour, there are both in Japanese and English and you can even arrange a private visit with your group of friends. The money from your ticket will go to the Tower Preservation Project, so in some way, you will be helping to keep it alive, even if no one knows for how long.

Fortunately, there is hope. Even if the tower cannot remain in its current location, the Nakagin Capsule Tower Preservation and Conservation Project will ensure that it is moved to another location, maintaining the essence of the building as much as possible. Metabolism and Kurokawa’s theory believed in an architecture that did not depend on the land. The building could then metabolize elsewhere since indeed, the needs of the population have changed. Maybe Kurokawa, Watanabe, and Metabolism weren’t so wrong, after all.

Book your guided tour of the Nakagin Capsule Tower in English or Japanese.

Buy the book ‘Nakagin Capsule Style’ on Amazon.

Thanks to Yuka Yoshida, Tatsuyuki Maeda, and the Nakagin Capsule Tower Preservation and Restoration Project for providing the information for this article, and for the incredible work they do to keep the tower alive.

Proofreading: Jasmina Mitrovic

( 人・ω・)